01.

Svetlica Tiny Tapers: tailor-made to fit

Jens H. Quistgaard’s

Dansk Designs candleholders

We have fallen so deeply in love with Jens Quistgaard’s candleholders that we decided to create special candles just for them. (Funnily enough, this is almost exactly how one of Dansk Designs’ ads from the 1960s began.) We’ve prepared two types of candles in different lengths, plus a few vintage candleholders if you don’t have one at home.

02.

I. A boxed set of 36 candles, each 35 cm long, designed especially for the “Spider.” Since this candleholder holds 12 candles at once, one set gives you three full displays. Each set is available in two options: with natural and dark beeswax dots.

II. A set of 12 long 50 cm candles that pair beautifully with the “Onion” candleholder. This candles come with dark dots.

Tiny Tapers, 35 cm

Set of 36 candles in a box (Dark dots)

Tiny Tapers, 50 cm

Set of 12 long candles

03.

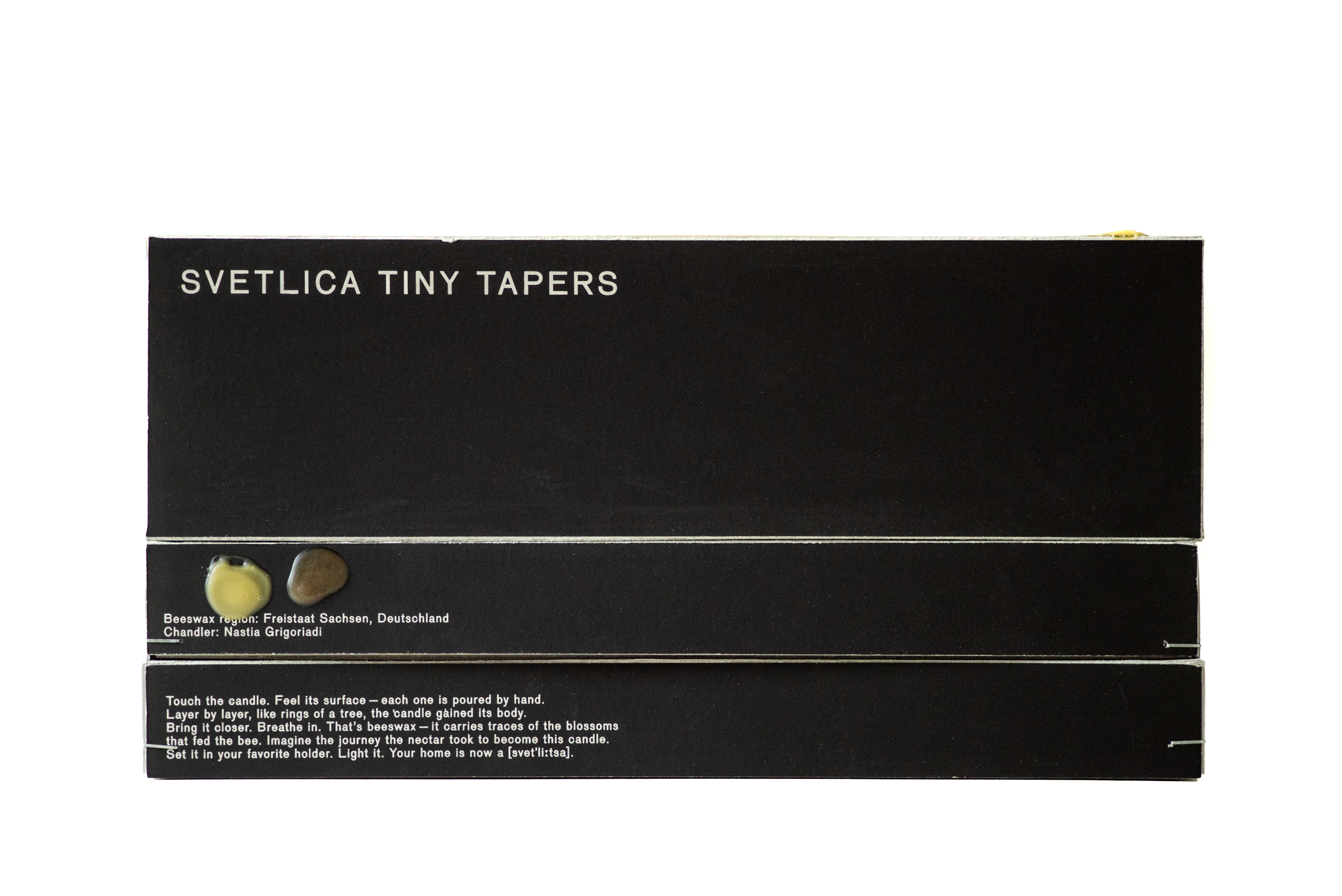

Svetlica Tiny Tapers, 35 cm. Set of 36 candles in a box.

They fit most of Quistgaard’s candleholders nicely, as well as others, such as Digsmed candleholders from the 1960s.

They fit most of Quistgaard’s candleholders nicely, as well as others, such as Digsmed candleholders from the 1960s.

Package design: handmade cardboard boxes with silk-screen printing.

04.

You can order the candleholders together with the candles. In our Vintage section, we’ve selected a number of “Spiders” and “Onions” ready to accompany their new light.

Candleholder, 1963

Candleholder, 1963Cast Iron

Dansk Designs

Design by Jens H. Quistgaard

“Onion” Candleholders (pair), 1964

Silver-Plated Brass

Dansk Designs

Design by Jens H. Quistgaard

Candleholder

Teak, Cast Iron

Digsmed

“The Snowflake NR 343 Made in Sweden” Candleholder

Cast Iron

Made in Sweden

SOLD

05.

Light Made by Hand: Jens H. Quistgaard, Dansk Designs, and the Candle as a Measure of Life

I. Objects That Gather Space

Some objects seem larger than they are.

A Jens H. Quistgaard candleholder, photographed alone, resists scale. It could be imagined as a small tabletop object, or—just as easily—as a monumental sculpture placed in a public square. Wherever it stands, it gathers space around itself.

This sculptural presence was never incidental. Quistgaard repeatedly described himself not as a designer in the architectural sense, but as a sculptor working with everyday things. Even straight lines, he insisted, should have a beginning and an end—slightly curved, slightly alive. Weight mattered. Balance mattered. Trust mattered: the assurance that a slender candlestick would not fall, despite its apparent fragility.

For Quistgaard, usefulness did not contradict beauty. On the contrary, beauty was what made an object believable, something you would want to live with, touch, and light again and again.

A Jens H. Quistgaard candleholder, photographed alone, resists scale. It could be imagined as a small tabletop object, or—just as easily—as a monumental sculpture placed in a public square. Wherever it stands, it gathers space around itself.

This sculptural presence was never incidental. Quistgaard repeatedly described himself not as a designer in the architectural sense, but as a sculptor working with everyday things. Even straight lines, he insisted, should have a beginning and an end—slightly curved, slightly alive. Weight mattered. Balance mattered. Trust mattered: the assurance that a slender candlestick would not fall, despite its apparent fragility.

For Quistgaard, usefulness did not contradict beauty. On the contrary, beauty was what made an object believable, something you would want to live with, touch, and light again and again.

II. Dansk, Like Vodka

When Jens Quistgaard and the American entrepreneur Ted Nierenberg discussed naming their company in the early 1950s, Quistgaard rejected anything too literal. Not “Danish Design.” Instead: Dansk.

“Dansk,” he explained, worked the way vodka worked in America: foreign, slightly exotic, pronounced incorrectly, and therefore memorable. The word carried its origin visibly, like Cyrillic letters on a bottle label. People noticed it. They talked about it. They repeated it.

The now-famous logo with four ducks performed a similar function. It was humorous, unmistakably Danish, and subtly autobiographical. More importantly, it suggested a family of objects—a shared language across materials, scales, and functions. Quistgaard insisted on this internal coherence and personally guarded it as Dansk’s sole chief designer.

“Dansk,” he explained, worked the way vodka worked in America: foreign, slightly exotic, pronounced incorrectly, and therefore memorable. The word carried its origin visibly, like Cyrillic letters on a bottle label. People noticed it. They talked about it. They repeated it.

The now-famous logo with four ducks performed a similar function. It was humorous, unmistakably Danish, and subtly autobiographical. More importantly, it suggested a family of objects—a shared language across materials, scales, and functions. Quistgaard insisted on this internal coherence and personally guarded it as Dansk’s sole chief designer.

III. A Sculptor Among Manufacturers

Quistgaard belonged to a rare category in postwar Scandinavia: a designer fully engaged with industrial production, yet unwilling to surrender artistic autonomy. He worked alone. He had no studio of assistants. He collaborated closely with foundries, carpenters, metalworkers—but never with other designers.

When Ford offered him a position in the late 1950s, with the condition that he would co-design alongside others, he walked away. Working with engineers was acceptable. Working with fellow sculptors on the same “object,” as he saw it, was not. Design, for him, was indivisible.

This insistence on independence later became a source of conflict within Dansk itself. Business logic and artistic conviction increasingly collided. But the tension was already present at the beginning: Quistgaard believed you could not create convincing objects “by the clock.” Time was not a resource to be optimized—it was a condition of quality.

When Ford offered him a position in the late 1950s, with the condition that he would co-design alongside others, he walked away. Working with engineers was acceptable. Working with fellow sculptors on the same “object,” as he saw it, was not. Design, for him, was indivisible.

This insistence on independence later became a source of conflict within Dansk itself. Business logic and artistic conviction increasingly collided. But the tension was already present at the beginning: Quistgaard believed you could not create convincing objects “by the clock.” Time was not a resource to be optimized—it was a condition of quality.

IV. Learning from Materials

Quistgaard never attended an academy. From early childhood, he learned by handling materials directly: wood, clay, steel, bronze, stone, silver—often all at once. His father encouraged making. His mother, a painter, instilled respect for craft.

This early intimacy with matter shaped everything that followed. For Quistgaard, form was inseparable from material. Wood suggested one kind of solution, cast iron another. Nothing was arbitrary. Even his architectural details—teak latticework, rhythmic grids—could be traced back to shipbuilding traditions and the practical logic of light, air, and safety at sea.

This early intimacy with matter shaped everything that followed. For Quistgaard, form was inseparable from material. Wood suggested one kind of solution, cast iron another. Nothing was arbitrary. Even his architectural details—teak latticework, rhythmic grids—could be traced back to shipbuilding traditions and the practical logic of light, air, and safety at sea.

V. An Island Without Electricity

At thirty-seven, Quistgaard bought a small, uninhabited island off the coast of Funen. He designed a modest stone house with a steep red-tiled roof and a separate workshop. There was no electricity.

This was not a romantic gesture, at least not primarily. He considered the alternative—electric pylons crossing the landscape—an aesthetic violation. Living without electricity was, to him, the lesser compromise.

Candles were therefore not decoration. They were necessity.

In the evenings, the house was lit by paraffin lamps and candlelight alone. The atmosphere that later generations would label hygge was born not from styling, but from constraint. It was here, in this electrically dark space, that Quistgaard began thinking seriously about candles and candleholders as a central category of modern domestic life.

This was not a romantic gesture, at least not primarily. He considered the alternative—electric pylons crossing the landscape—an aesthetic violation. Living without electricity was, to him, the lesser compromise.

Candles were therefore not decoration. They were necessity.

In the evenings, the house was lit by paraffin lamps and candlelight alone. The atmosphere that later generations would label hygge was born not from styling, but from constraint. It was here, in this electrically dark space, that Quistgaard began thinking seriously about candles and candleholders as a central category of modern domestic life.

VI. Designing for the Flame

Quistgaard believed candles belonged naturally on a well-set table, just as a fireplace belonged in a home. From the late 1950s onward, he designed dozens of candleholders: cast iron, brass, silver-plated brass, glass. Single flames and clustered constellations. Vertical, tilted, rhythmic, asymmetrical.

Some designs were playful; others austere. All explored contrast—between straight and organic elements, between mass and slenderness, between stability and apparent imbalance.

He even designed a special drip-free taper candle with a long burning time, engineered specifically for tilted holders. The candle was not an accessory. It was part of the system.

Some designs were playful; others austere. All explored contrast—between straight and organic elements, between mass and slenderness, between stability and apparent imbalance.

He even designed a special drip-free taper candle with a long burning time, engineered specifically for tilted holders. The candle was not an accessory. It was part of the system.

VII. Advertising the Dream

In America, Dansk’s objects quickly escaped the confines of design discourse. They appeared in fashion magazines, lifestyle ads, interiors staged for an affluent, modern audience. By the early 1960s, Dansk advertisements were photographed by Bert Stern; illustrated by a young Andy Warhol; and later shot by Irving Penn.

These images abandoned strict functionalism in favor of atmosphere, longing, and identity. Dansk openly acknowledged that people do not buy objects for rational reasons alone. They buy them because they recognize something of themselves—or something they wish to become.

These images abandoned strict functionalism in favor of atmosphere, longing, and identity. Dansk openly acknowledged that people do not buy objects for rational reasons alone. They buy them because they recognize something of themselves—or something they wish to become.

VIII. Simplification Without Impoverishment

Quistgaard often returned to a phrase that became his quiet motto: simplification without impoverishment.

Beauty, for him, was not decoration. It was a source of joy, hope, and something he described as almost spiritual. Beauty reminded us that there is something larger than ourselves—something we momentarily participate in through the act of looking, touching, lighting.

This belief separated him from strict functionalism. Function could be beautiful, yes—but beauty also had value of its own.

Beauty, for him, was not decoration. It was a source of joy, hope, and something he described as almost spiritual. Beauty reminded us that there is something larger than ourselves—something we momentarily participate in through the act of looking, touching, lighting.

This belief separated him from strict functionalism. Function could be beautiful, yes—but beauty also had value of its own.

IX. Svetlica and the Time of Making

Svetlica’s candles are made without molds, using a centuries-old pouring technique. Wax is slowly layered around a wick, allowing the candle to grow over time. This makes almost any length possible—35 cm, 50 cm, 110 cm, even 150 cm—but it also makes each candle labor-intensive and irreducibly handmade.

Each candle is made by Nastia Grigoriadi herself, in a small workshop. No two are identical. Small differences in weight, surface, and rhythm remain visible. Dark specks in the beeswax bear witness to its origin: nectar transformed by bees, then by hands.

Like Quistgaard’s practice, this is work that resists acceleration. You cannot do it “by the clock.”

Each candle is made by Nastia Grigoriadi herself, in a small workshop. No two are identical. Small differences in weight, surface, and rhythm remain visible. Dark specks in the beeswax bear witness to its origin: nectar transformed by bees, then by hands.

Like Quistgaard’s practice, this is work that resists acceleration. You cannot do it “by the clock.”

X. Tiny Tapers for Dansk Designs

The Svetlica Tiny Tapers were created specifically for Jens Quistgaard’s candleholders from the 1960s—especially the Spider and the Onion. They are tailor-made, not only in diameter and length, but in spirit.

These candles acknowledge Quistgaard’s understanding of the flame as part of the object, not an afterthought. They accept that a candleholder is incomplete without a candle, and that a candle, too, has a form, a duration, and a responsibility.

In pairing Svetlica’s poured candles with Dansk Designs’ sculptural holders, we are not recreating the past. We are continuing a conversation about slowness, material honesty, and the quiet power of light.

A conversation that once took place on a small island without electricity—and that still begins, every time, with striking a match.

These candles acknowledge Quistgaard’s understanding of the flame as part of the object, not an afterthought. They accept that a candleholder is incomplete without a candle, and that a candle, too, has a form, a duration, and a responsibility.

In pairing Svetlica’s poured candles with Dansk Designs’ sculptural holders, we are not recreating the past. We are continuing a conversation about slowness, material honesty, and the quiet power of light.

A conversation that once took place on a small island without electricity—and that still begins, every time, with striking a match.